Learning in Writing: An Analysis of High School to College Writing

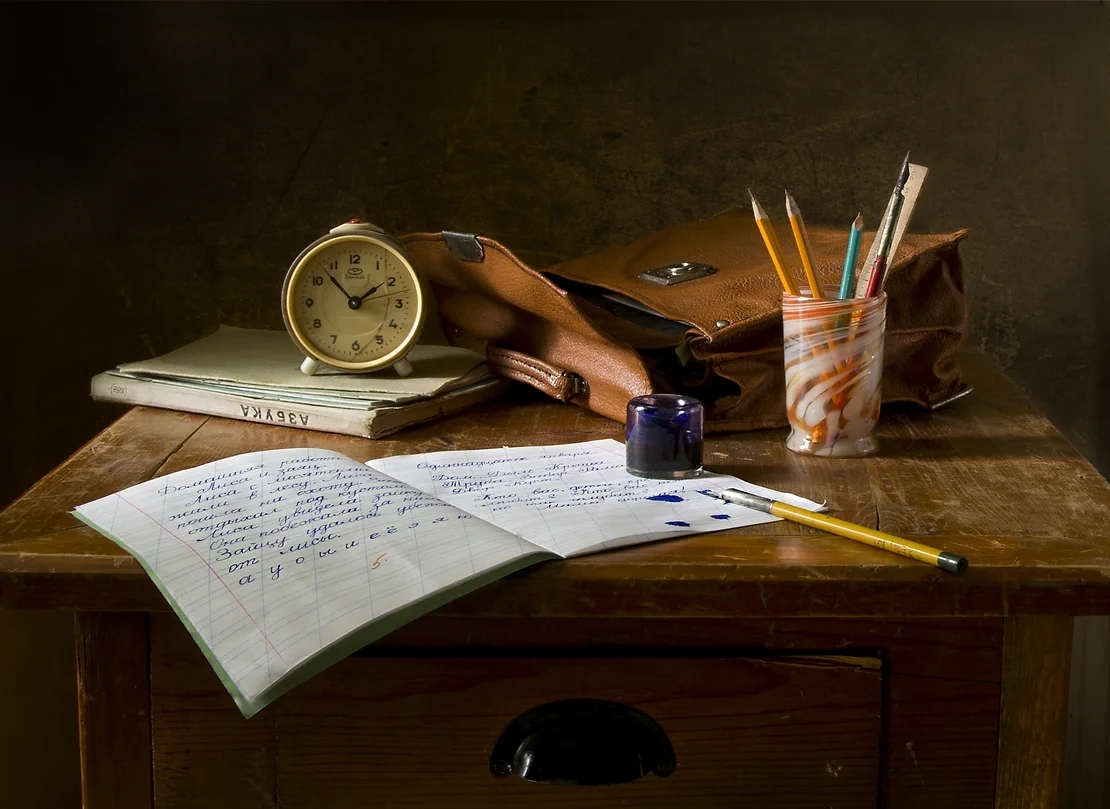

Photo by Unknown

Photo by Unknown

Learning can happen in a multitude of different ways. One of those ways that is overlooked by many is through writing. In threshold concept 4.0 All Writers Have More to Learn (TC 4.0), Shirley Rose explains that during those fundamental years of high school where students are gaining new knowledge about math or science, the writing curriculum is never updated. Students learn the same type of five-paragraph essay every year because schools want to generalize writing so that one style fits every situation when in reality, that is not the case (Rose 60).

According to TC 4.0, due to these repeated writing circumstances throughout education, writers themselves fail to realize that there is much more they can learn about writing. Thus, they have trouble comprehending the fact that they will never be able to learn all there is to know about writing. There will always be a different circumstance where a new writing approach can be enacted, whether it be through college courses or professional disciplines (Rose 59). Writers are often perfectionists and the news that they can’t ever become experts in their craft due to habituated learning surrounding writing is quite troublesome.

Other TC’s such as 1.7 Assessing Writing Shapes Contexts and Instruction further expand on this idea of generalizing writing, as it is the writing criteria that students are assessed on in school that shape their writing experience up until high school graduation (Scott and Inoue 30). In reality, these assessments of “good writing” (Scott and Inoue 30) are harmful to their growth as a writer. They do not allow for creativity or development as a writer (Scott and Inoue 30-31).

As a writer myself who has experienced the lack of variation of writing curriculum in schools, I have also experienced the slight shock upon coming to college and seeing how much I don’t know as a writer. I think it is important to highlight others’ experiences with this as well.

To research this topic further, I surveyed two groups—high school and college students— via Google Forms on various aspects of learning in writing. The main goal of the survey was to highlight the difference between high school and college writer learning experiences. I received six high school student responses and four college student responses. I’ve identified three general areas where the two groups differ: feelings on assessments of writing, what they are learning in writing, and their relationship between the writer and the reader.

Rubrics: Friend or Foe?

Through analyzing the responses to my survey it became evident to me that high school vs. college student feelings on assessment of writing (rubrics) were mixed. I asked both groups whether they found rubrics to be helpful for their learning and growth as a writer. While some high school respondents viewed rubrics in a positive light, their reasons varied. High school respondent 1 touched on how not everyone takes feedback the same way and it depends on the level of criticism the rubric provides for how the writer will react. High school respondent 4 had experience with “clear and detailed” rubric feedback that fostered their growth as a writer, while a few of the other respondents expressed feelings of frustration with rubrics as they felt inhibiting to them, not letting them reach their full writing potential due to their constricting guidelines. This demonstrates TC 3.3 Writing Is Informed by Prior Experience. Since some of these students have had positive outcomes from rubrics in the past, they are in favor of them, whereas the students who have seen negative effects on their writing from them express dislike towards rubrics.

High school respondent 3 brought up an interesting point on how restricting rubrics can be: “Sometimes I feel like I can’t write in a certain direction that I’m compelled to write in because it won’t get me a good grade.” This reflects TC 2.5 Writing Is Performative, pretty blatantly. This student feels the need to adjust their writing to fit the guidelines of the rubric, when they are being pulled in a different direction by their writing instincts, causing them to write a performative piece, rather than a genuine one (Lunsford 43-44). The student then goes on to say that overall the rubrics are fair and cause them to learn. However, based on their response I feel as though the only thing they are learning is how to receive a good writing grade from a teacher. While that is a valuable skill that will take a writer far, it does not foster growth as a writer, which is an issue in itself.

It’s almost as if college students “unlearn” the standards of the high school rubric within college writing. When asked the same question regarding high school rubrics, half of the college respondents answered how I predicted. College respondent 3 described rubric guidelines as “constricting and rarely had much in terms of what the teacher wanted the essay to be.” This correlates with the response of high school respondent 3 as this college student felt the inhibitory effects of rubrics as a writer. The mention of the vague requirements that the rubric supplied is important to note as that further demonstrates how students need to fulfill these checkboxes, but have little idea what they mean, enforcing the power dynamic between teachers assessing writing and students illustrated in TC 1.7 Assessing Writing Shapes Contexts (Scott and Inoue 30-31). College respondent 4 ignored rubrics in high school because they “couldn’t write well while trying to fit in those boxes” but they believe some form of guidelines is necessary. They note the idea that “in college because there isn’t a one size fits all grading for essays you get better feedback from professors.” I think the creators of school writing curriculums need to start questioning what they are teaching students. Is it better to have uniform writers contorted to fit boxes or distinct writers with their own voices?

College respondent 2 surprised me, as they expressed that their high school wasn’t strict with rubrics which put them at a “disadvantage” in college as they had to “quickly adapt” to the “harsher grading scales.” While this has not been my experience as I consider college grading scales to be less strict, it demonstrates TC 4.0 All Writers Have More to Learn (Rose 59-61). This student learned how to become successful in a college writing environment after not being prepared in high school. They are currently crossing the threshold of this concept. However, some students have not yet crossed the threshold for this concept in high school and college.

Learning in Writing: Concrete to Open

Based on the survey, high school students tend to have a more concrete mindset in terms of the information they learn about writing, which makes sense knowing their heavy association with rubrics and good grades. I asked these high school students if their writing curriculum changes at all each year. Most of the responses I received highlighted learning new rhetorical terms such as “anaphora” and “zeugma” from AP classes, as well as the mention of the one-hour synthesis essays that rear their ugly head in AP Language and Composition (APLAC). These responses didn’t shock me, as they are typically what is to be expected of high school students. Still, after being in college for a whole year and having my writing focus shifted from technical errors to content and process, it was a surprising reminder of what writing was like before college. High school respondent 1 spotlighted that the writing information in the curriculum may even be “outdated”, bringing up the issue of he/him or she/her pronouns being the “correct” way of writing when they/them pronouns are more convenient and can be gender inclusive. Respondent 5 claimed the curriculum is “stagnant.”

If the high school writing curriculum can’t even change enough for students to highlight information they learn other than rhetorical devices or other minimal changes, how is it supposed to address areas of pronouns and gender or prepare students for writing post high school? True learning through writing isn’t taking place till college when it should be earlier. While grammar, speedy persuasive essay skills, and rhetorical phrases make writing stronger, I have learned that it is the initial process that matters most. Without defining the process of writing, none of those other skills can reach their highest potential.

I asked the college student group how writing in college differed from writing in high school. There were some contradicting opinions. College respondent 1 hasn’t felt a difference yet, meaning they haven’t crossed TC 4.0 All Writers Have More to Learn, as they didn’t learn anything groundbreaking yet in college writing. College respondent 2 describes college writing as “more structured and well organized” and that there is an expectation to know and perform different styles of writing well. My experience has been more similar to respondent 4 who thought college writing was less structured and that they can show their “style/personality” more in their writing. I feel like I have been able to write about topics I care about more in college, whether that be through choosing my essay topic, organization style, or writing articles for the Arts & Entertainment section of the paper. My writing has been less structured/confined, which has allowed me to take it in directions I haven’t before. While the different styles and assignments may be daunting, I find that professors are willing to meet and provide feedback on my writing. I know that this is not the experience for everyone, so I feel fortunate.

College respondent 2 also mentioned that an important thing they have learned is “that it’s okay…and maybe even preferred for the first draft not to be good.” This is something I had to learn myself as well. As a writer, I care about the words I’m putting on the page, and I sometimes attribute too much meaning to them. College respondent 3 expands on this idea, observing that college writing is a “painstaking…process” that teaches the importance of the writer diving into their thoughts and topic of writing. While there is a mix of responses on whether or not these college students feel they have grown as writers yet, this is a clear learning curve to adapt from high school to college writing. There is a transfer from very concrete to more open learning, which causes college writers to develop connections to writing that high school writers haven’t yet.

The Writer and The Reader

One of the biggest things I noticed from my survey was that high schoolers separate the writer and the reader and do not see them as related. When asked to define “good writing” many focused on the reader with responses such as: “…something that conveys an idea an emotion or thought in a way that is clear and influences the reader”, “…has a profound/emotional effect on the reader”, “…grasps the reader’s attention” and “…it is important that the reader knows the writer has full control of what they’re writing.” In college, writers are taught to connect the reader and the writer, as each affects each other. In TC 1.3 Writing Expresses and Shares Meaning to Be Reconstructed by the Reader, Charles Bazerman explains that the reader will not always receive the same message the writer is trying to convey. The reader can never fully understand the content of the writer’s mind. Readers have experiences of their own that may attribute different meanings to the writer’s words than they intended (Bazerman 21-23), so while these high school students are talking about the writer pleasing the reader, they don’t realize how difficult that is to do. Therefore the writer has full control over the words they write, but not full control over how they are interpreted. Good writing goes beyond the reader and the writer and becomes a blend of shared experiences of both of them.

College students responded a little differently when asked to define “good writing.” College respondent 3 groups the writer and reader together rationalizing “good writing” as “…writing that is pleasing to both the author of the work and the reader of the work.” I believe this is a strong definition, however, authors are often very critical of themselves (myself included) so it is hard to have a work that pleases both the author and reader. Still, college students may be getting to that point now that they are writing pieces they enjoy. The other college respondents still had more focus on the reader similar to high school students but mentioned concepts of “relatability, “emotional impact”, engagement and learning. The high school respondents focused more on grammar and other mechanics to define good writing and while the college students included those as well, it was not their main focus.

All Writers Have More to Learn

Good writing is subjective. It is defined by prior and current experience. The definition of “good writing” is ever-changing as writers are thrown into new writing situations all the time, especially in college. The assessment of writing through rubrics detaches high school students (as writers) from the readers of their work. They are not focused on their own growth as a writer as they are conditioned to performative writing for a grade. Therefore, this separation of writer and reader is a natural byproduct of that conditioning. Their writing experience is dictated by their teachers (the readers). Every piece of writing is performative in some way, but hopefully not to the grave extent of high school essays. These college students are learning that growing as writers and focusing on the writing process is more important than racing to the outcome of the project for a grade. While this learning will produce better writers, having this period of growth happen earlier on in students’ writing careers would be more ideal and prepare them better for college and the professional world. The sooner writers are introduced to the concept that they will forever be learning about writing, the sooner they can start and internalize this learning process, even though the endless void of writing knowledge and practice may be troublesome. It is better to produce writers who are works in progress than writers who are stagnant and unlearned.

References

Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Elizabeth A. Wardle, editors. Naming What We Know: Threshold

Concepts of Writing Studies. Utah State University Press, 2016.

Bazerman, Charles. “1.3 Writing Expresses and Shares Meaning to Be Reconstructed by the

Reader.” Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Elizabeth A. Wardle, pp. 21-23.

Lunsford, Andrea A. “2.5 Writing Is Performative.” Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Elizabeth A.

Wardle, pp. 43-44.

Lunsford, Andrea A. “3.3 Writing Is Informed by Prior Experience.” Adler-Kassner, Linda, and

Elizabeth A. Wardle, pp. 54-55.

Rose, Shirley. “4.0 All Writers Have More to Learn.” Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Elizabeth A.

Wardle, pp. 59-62.

Scott, Tony and Asao B. Inoue. “1.7 Assessing Writing Shapes Contexts and Instruction.”

Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Elizabeth A. Wardle, pp. 29-31.